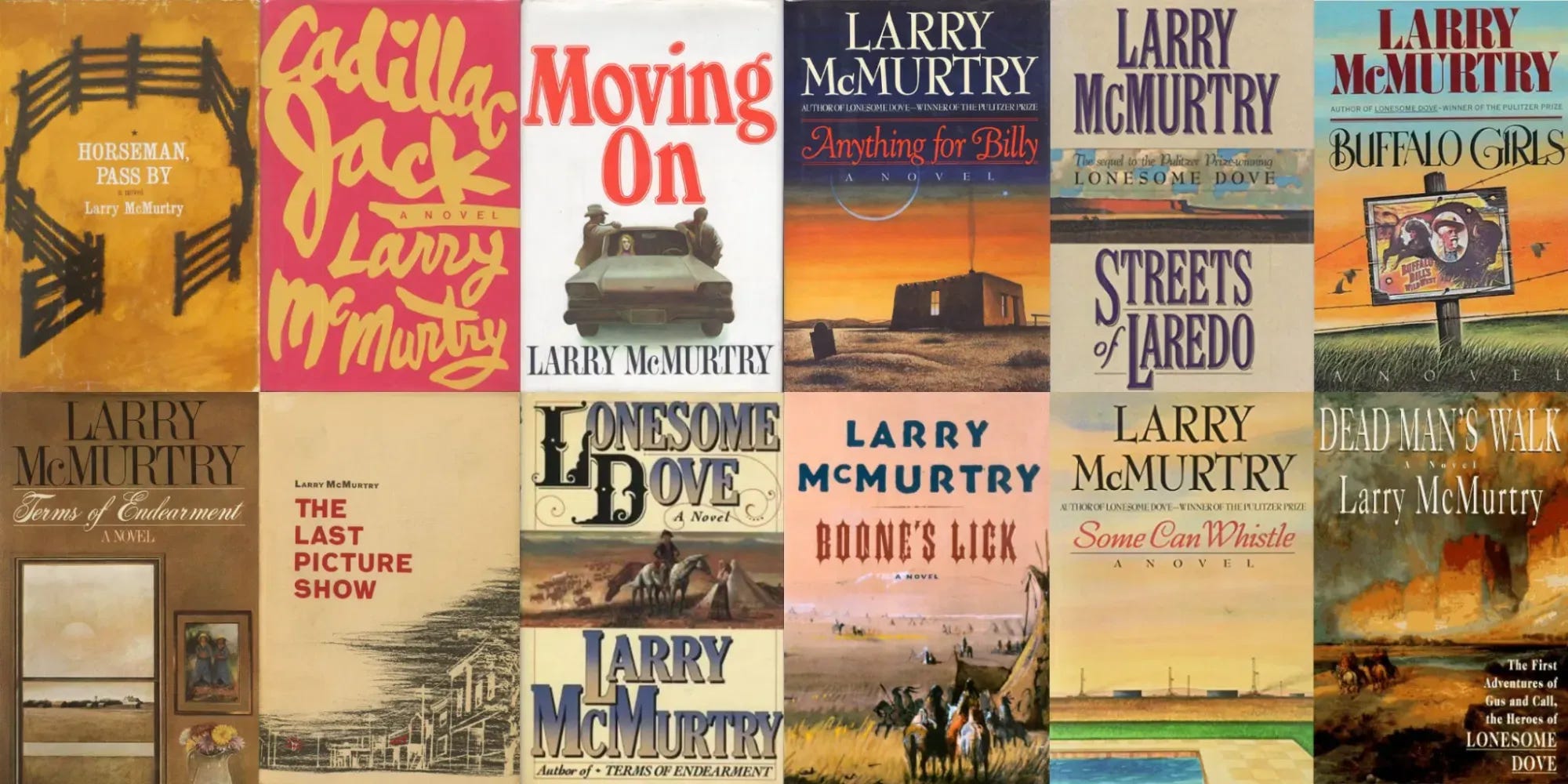

In a recent collection of essays about the life of Texas literary giant Larry McMurtry, the author of works such as The Last Picture Show and Lonesome Dove is depicted in a series of interconnected roles. These roles include inspiration, mentor, professor, disaffected cowboy, friend, trailblazer, book collector, curmudgeon, and advocate.

He was a man who insisted that the environment that he depicted (the West) was worthy of portrayal, analysis, and enrapturing narrative. More than anything else, they portray him as one of the most captivating writers who has ever lived. This is something that cannot be denied by anyone who has read McMurtry’s works. His compositions first evoke feelings, and then they provoke thought in the reader.

George Getschow, a professor of journalism at the University of North Texas, served as the editor of Pastures of the Empty Page, which was released on September 5 by the University of Texas Press. McMurtry’s legacy in Texas literature has been the subject of a number of panels that have recently been held; another one is scheduled to take place at Interabang Books on Tuesday, January 9, at six o’clock in the evening. A conversation between Getschow and Michael J. Mooney, a journalist, a reporter for the Axios newsletter, and an occasional D writer, is scheduled to take place.

One can understand why one might want to attempt to analyze McMurtry’s legacy. The question of whether or not McMurtry, who passed away in 2021, would have enjoyed the book is a more challenging one to investigate.

It is possible that the response is not yes for a reason that is both evident and rather superficial. Given that McMurtry was a sour and self-deprecating individual who frequently referred to himself as a “minor regional novelist” for reasons that, as the articles point out, are a combination of irony and true self-criticism, it is possible that he would have considered such a protracted project that was focused at praising him to be a waste of time. A good number of the authors of these pieces knew McMurtry personally in some way, and they would gladly disregard any protests that were made against him.

However, there is a more significant problem that arises with such a compilation. If there is a single thread that can be found throughout McMurtry’s books, it is that they frequently take the form of a call to refrain from romanticizing and mythologizing concepts just due to the fact that they are vanishing. According to his point of view, the romanticism that we applied to our images of the old West posed a number of possible risks. There was something in McMurtry’s described worlds that could be intriguing, complicated, humorous, and once treasured; yet, this did not inevitably make it excellent, or in certain cases, even important to retain in perpetuity.

Very few of these articles avoid sliding into pure respect, not only for McMurtry but also for the craft and ambition of writing writ large, using McMurtry as an avatar for a tradition that is perceived as universally excellent and free of bias. In fact, very few of these essays even seek to resist going into pure reverence.

These accounts of links to the great writer are characterized by an air of self-importance that permeates those accounts. There are a few of the essays that are caught in the act of weaving McMurtry into their own constructs of mythology.

“His career was both intimidating and inspiring for many Texas writers, particularly those of my generation working as soon as they set out in the shadow of his achievements,” writes Stephen Harrigan, a novelist and longtime journalist with Texas Monthly. Harrigan has been with Texas Monthly for a long time while also being a journalist.

In the beginning of his essay, Skip Hollandsworth says, “When I was a kid, I saw the author of Lonesome Dove for the first time on the streets of Archer City.” It was a meeting that would have a lasting impact on the rest of my life. In the beginning of a tale that was published in Texas Monthly in 1991, he stated that he “never made it past page 47 of Lonesome Dove.”

Geoff Dyer applauds McMurtry’s prose for not “drawing attention to its own merit” but then he namedrops as he relates that he told Zadie Smith to read Lonesome Dove, an anecdote that contributes little besides her (admittedly snooty) response that she doesn’t like Westerns.

An opportunity to take the long road toward hinting to or even outright stating one’s own accomplishments is presented whenever there is a discussion about having a mentor, or even just discussing someone who is an inspiration. The authors of these essays are highly skilled writers who are writing about an even more accomplished writer; nonetheless, reading about their bylines and honors will not give anyone with even a glimpse of the richness that the authors of these essays themselves discovered in McMurtry’s writings when they were younger. The fact that William Broyles, the founding editor of Texas Monthly, was influenced by McMurtry is not only a fact that anyone would have already guessed to be true, but it is also an interesting fact.

All of this makes you wonder who precisely this book is for, and it comes very near to making it abundantly evident that it is created solely for the purpose of being read by other authors. These essays will provide glimpses and quirks and no-bullshit motivations of a literary giant who, as the book hammers home more than any other point, changed the literary landscape and possibilities for Texas. This is true for any writer who writes because they are drawn by some semi-articulable sense of the craft’s importance, which is to say, which covers the majority of writers.

The editor of the book, Getschow, is also an established journalist who was the head of the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference held at the University of North Texas. He frequently discusses and writes about “literary nonfiction.” It is the pieces in Pastures that are more fact-focused and less meandering that are the ones that provoke the most thought, despite the fact that the name itself suggests a kind of elevated version of what would otherwise just be referred to as journalism.

The author of Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal biography of the Texas Rangers, Doug J. Swanson, analyzes McMurtry’s criticism of the previous definitive text on the Rangers, which was a glowing biography written by Walter Prescott Webb that solely depicted them as righteous and valiant. McMurtry’s criticism was published in 1968. “[Webb] records virtually no instance in which a Ranger treats either a Mexican or a Negro as anything but inferior, and he seems to accept the still-common assumption that a Ranger can tell whether a Mexican is honest or dishonest simply by looking at him.”

Within the context of his essay, Swanson, who is as well aware of the shortcomings of the Rangers as anybody else, draws attention to the ways in which McMurtry undermines the notion that the Rangers’ ranks are heroic knights of the Texas plains in Lonesome Dove. By doing so, as well as by highlighting McMurtry’s distaste for Webb’s telling, Swanson enables the reader to strike a balance between McMurtry’s good intentions and the manner in which the Lonesome Dove was received by the general audience.

The purpose of McMurtry’s writing was to make fun of the Western cowboy and the Texas Ranger, but he simply made his writing too fascinating, and as a result, his readers were compelled to spend an excessive amount of pages with characters they were not supposed to like. The result is that Gus and Call, two Texas Rangers with questionable morals and levels of competency, are often revered, just as Lonesome Dove is still used as nostalgic inspiration for the old West, most notably by Taylor Sheridan’s hit show Yellowstone and its prequel spin-off 1883.

Andrea Long Chu argues in New York Magazine that “Sheridan shunts the ambivalence of Lonesome Dove, at the last moment, into frank colonial sentimentality.” This is a development that McMurtry most likely would not be pleased with, but he most likely grown accustomed to it.

Later on, a reporter for the Dallas Morning News named Dianne Solis takes McMurtry to task for the stereotypical portrayal of Mexicans that he made, despite the fact that he appeared to be aware of the situation.

Solis explains, “As a writer with Mexican roots, I cannot and will not tolerate such racism on the written page. Many people may excuse such racism on the written page as a reflection of the times in which it was written.”

At the end of the day, despite the fact that it has several shortcomings, Pasture of an Empty Page is still rather addictive. (It goes without saying that I come from a writing background.) There are important biographical data about McMurtry’s life and career that are presented in a manner that is less formulaic, if more repetitive, than they would be in a straightforward biography. These details are offered to the reader.

The book shows a man who lived a singular life, provided by way of glimpses into McMurtry’s writing process, his decades as a nearly unparalleled book collection, and the cattle range origins that Getschow highlights in his essay.

Diana Ossana, McMurtry’s 30-year collaborator and co-screenwriter of Brokeback Mountain, wrote a moving essay about their relationship, the origins of their collaborations, and the specifics of McMurtry’s darkest period of depression. The specifics of this chapter are shockingly personal in comparison to the other writings that are included in the book. Likewise, Mike Evans, a student of McMurtry in 1964, who would go on to marry McMurtry’s ex-wife and play a part in raising his son, James McMurtry, writes of Larry in a way that reflects the intimacy of their relationship.

The hardest part about reading Pastures of the Empty Page is never getting to read McMurtry in its pages. Instead, he is the subject of writers plenty capable of stirring something in a reader, so capable that someone reading this collection who has never actually read McMurtry must think that his writing is literal magic, able to do something even more powerful than any of these essays could.